The night had barely settled over Igbara-Oke village in Ondo State when eight months pregnant Oluwatayo Akin (not real name), groaning in pain, was helped out of a rusting tricycle and into the dim, crumbling compound of Igbara-Oke General Hospital.

The facility was intended to be a place of healing, as it is the only public hospital serving this hilly, close-knit town in the state. But on that night, it became a place where time stood still and hope felt like a far-fetched promise.

Her husband, Akin, clutched her hand tightly, whispering reassurances he didn’t believe. His mother trailed closely behind, her wrapper tied tightly at the waist, already sensing that something was wrong.

Inside the hospital, everywhere was silent as darkness swallowed the corridors. There was no electricity, no backup generator humming. The emergency ward was a hollow shell, dimly lit by the flashlight on a nurse’s phone, revealing peeling walls, broken windows, and dust-covered shelves.

“I thought we had come too late. It was like walking into a forgotten place. No doctor. We only met some nurses pacing, confused, and unprepared for such a case,” Akin’s mother recounted.

The nurses on duty moved with a sluggishness that betrayed either exhaustion or inexperience, or both. One of them, a young woman with worry etched across her face, kept glancing at Oluwatayo, as if unsure what to do next.

For several hours, it was difficult for the nurses to help Oluwatayo as contractions had worsened while the pain had deepened. No help came since there was no doctor or specialist on duty.

While Oluwatayo’s family scrambled outside the hospital walls, inside, her condition was deteriorating. Her strength was fading with each passing minute. Her breath grew shorter. The baby stopped moving. The nurses finally admitted what had become obvious from the start: they couldn’t handle the case.

At around 1 a.m., they handed over a referral letter to the family. With no ambulance in sight, the family had to borrow a neighbour’s rickety car. Akin, now visibly shaking, cradled his wife in the back seat as they set off on the long, dark road to Akure, a nearly one-hour drive, over potholes and through pitch black.

They arrived at the Mother and Child Hospital in Akure just before dawn. This time, help came quickly. But by then, the ordeal had taken its toll. It was a miracle that Oluwatayo and her baby survived.

Near-death experiences

Akin’s mother, still shaken years later after the incident, didn’t hide her anger when speaking with our correspondent.

“When we got to the general hospital, it was all dark, and there was no light. We were asked to get fuel to power their generator set, which we did.

“After that, we were also given a list of drugs and other things to procure, many of which are not available at the pharmacy; we had to rush out and go to the homes of people operating pharmacy shops in the area.

“The hospital had nothing, and I wonder why the general hospital serving the community is that empty. We nearly lost her and the child,” she said.

For a businesswoman, Mrs Kemi Odunayo (not real names), her life was on the brink by the time she got to a general hospital in Akure after her referral from Igbara-Oke general hospital.

Nurses wheeled her in urgently, her chest heaving in shallow breaths as she was placed on oxygen. Doctors circled quickly, fighting to keep her alive after hours of neglect at the general hospital.

“The general hospital at Igbara-Oke couldn’t help. By the time we arrived in Akure, she was almost gone. They fixed her on oxygen immediately. I just stood there praying she would not die,” her husband, Odunayo, told PUNCH.

Hours later, the baby came, but the battle was only half won. Instead of the sharp cry that heralds new life, silence filled the room. The delay had stolen his first breath, leaving him a victim of birth asphyxia.

Odunayo said the moment nearly shattered them.

Recounting the harrowing experience, he said, “The baby didn’t cry when he came out. The doctors carried him away, and we feared the worst. We had gone through so much already, only for the baby to be fighting for his life.”

In the neonatal ward, tubes and machines became the child’s lifeline. His tiny chest rose unevenly, tethered to wires for weeks instead of his mother’s embrace.

For Odunayo and his family, the scars linger far longer than the hospital stay at the neonatal unit, a reminder of the hours wasted at Igbara-Oke hospital.

“The coming of a newborn that should have brought joy to the entire family became a season of pain,” Odunayo lamented.

Health experts say such delays are deadly. According to maternal health specialists, every lost minute in childbirth increases the risk of complications such as birth asphyxia, haemorrhage, or maternal death.

The World Health Organisation listed birth trauma among the top global causes of death. Birth trauma is distress experienced by a mother during or after childbirth, as well as the concomitant effects on the child, otherwise known as neonatal conditions.

“Birth trauma is not just about what happened during labour and the birth. It can also refer to how the mother is left feeling afterward,” WHO said.

But in Igbara-Oke, pregnant women who should draw strength from the secondary facility, investigation reveals, instead are trooping to the modest primary health centre in the community that has become their only refuge.

Expectant mothers’ plight

Some of the pregnant women who shared their experiences said their decision to use the Primary Health Clinic, Ifedore Local Government Area, was not about convenience but for adequate care.

With bitter memories of her first pregnancy, Kemi said her experience at the hospital as a first-time pregnant woman made her choice easy.

Kemi, now pregnant with her second child, said, “When I went into labour for my firstborn at the general hospital here, I was really in pain, and I thought I would die.

“Since then, I have used the health centre called Maternity. At least the health centre gives us a chance.”

In a chat, a pregnant mother, Mrs Morenike Adeyemi, said the facility remains a place she no longer trusts, adding that her last antenatal visit ended in frustration.

“The doctor wasn’t around, and the nurses told me to wait. I sat for two hours without being attended to. I left and promised never to return,” she recalled.

The 25-year-old fashion designer, who is in her second trimester, explained that she later registered at the health centre.

“The nurses may not have everything, but at least they are always there. They give us drugs and treat us with care,” she disclosed.

Corroborating the claims, a midwife at the health centre who preferred anonymity noted, “Here we prioritise our patients, particularly the pregnant women, and that is the reason why many residents don’t like going to the general hospital.

“Even, if we refer them, they’d insist they are not going there. They’d insist they want care here. Even pregnant women and sick children from JABU (Joseph Ayo Babalola University) come here.

“We have taken many deliveries of pregnant women who came here from JABU. People from neighbouring communities also prefer here,” she told our correspondent, who disguised as a husband who wants to register his wife for antenatal.

A maternal health specialist, Prof Chris Aimakhu, said general hospitals should serve as the referral point for primary healthcare centres, not the other way round.

“There are grades of health care facilities—you have the primary, then secondary (general hospitals), and then tertiary, like teaching hospitals. The higher you go, the more advanced the facilities, experts, and care should be,” he said.

But recurring cases and several accounts from residents in Igbara-Oke and neighbouring communities in the Ifedore Local Government Area of the state echo the painful familiarity of a hospital that has failed the people.

During a visit to the hospital on September 10, 2025, the first sight that greeted our correspondent was not a reassuring gateway to healing but an entrance marked by neglect.

The boundary walls were streaked with age and grime, while weeds and overgrown grass spilled into the roadside drain.

Our correspondent observed a faded signboard, partially hidden by foliage, during the visit, which struggled to announce the hospital’s presence.

Instead of offering comfort and order, the entrance projected abandonment and decay unworthy of a general hospital that should welcome patients with dignity and hope of proper care.

Except for the two men our correspondent met at the gate, a few steps into the hospital, one could mistake it for a deserted facility. Inside the compound, a faded direction signboard welcomes visitors before the sight of an abandoned pickup truck.

During the visit, it was also observed that the building housing the Accident and Emergency Department, which also doubles as the General Outpatient Department, appeared frail, with cracks snaking across its walls, giving the premises an abandoned air.

Inside, the equipment meant to save lives told its own story of neglect. Vital machines were sighted as either outdated or broken, their once-gleaming bodies now rusted and covered in dust.

Stretchers with torn leather sat idly in corners, while oxygen cylinders looked more like relics than tools of emergency care. Rather than inspire confidence, the department, which serves as the first point of call for critically ill or injured patients, steals hope from patients.

Pharmacy turned shelter

Probing further, a visit to the hospital’s pharmacy revealed a disturbing reality, with the outside overrun by weeds. Rather than a well-organised space, the pharmacy is riddled with lapses that raise serious concerns about patient safety.

It was discovered that instead of neatly arranged shelves, boxes of drugs were stacked loosely on dusty wooden planks, without clear labels or a system to separate medicines.

It was observed that the absence of order not only increases the risk of dispensing errors but also suggests a lack of routine inventory checks.

Equally troubling was the intrusion of non-clinical activities into the pharmacy. Personal clothes and bags were draped carelessly over plastic chairs within the dispensing area, blurring the line between professional workspace and private storage.

This lack of separation exposes medicines to contamination and undermines the facility’s integrity. The two staff members who manned the pharmacy when our correspondent visited were more concerned with chit-chat than serious business.

Investigations, however, reveal that the abandoned pickup truck at the entrance serves as the delivery van used to bring drugs and other consumables, including chemicals used at the mortuary, from Akure down to the facility.

“Most patients are asked to go get the needed drugs outside the hospital. It’s been a while since we got a drug supply in the hospital,” a nurse in the hospital told our correspondent.

Troubling lapses

While at the hospital, our correspondent observed troubling lapses that raise serious questions about the standard of care and patient safety within the facility.

At the entrance to the male and female wards, the first impression was one of neglect. Peeling paint and cracked walls lined the corridor. Instead of a clean and controlled environment, the space looked cluttered and unsafe.

Inside the wards, the situation was no better. Though no patient was on admission, our correspondent observed that beds were crowded together with very little spacing, leaving potential patients with no privacy and creating a fertile ground for cross-infection.

Mosquito nets sighted hung untidily above thin mattresses, suggesting poor upkeep. More concerning was the absence of essential medical equipment like oxygen cylinders, suction machines, or bedside monitors, even though these are critical in any general ward for emergencies.

Waste handling also appeared inadequate in the wards. The open yellow bucket inside the ward was being used for disposal, as there were no proper colour-coded clinical waste bins. Combined with poor environmental hygiene, this undermines even the most basic standards of hospital infection prevention.

Investigation reveals that these systemic lapses not only compromise patient dignity and comfort but also actively endanger lives.

For a facility meant to provide healing and hope through adequate care, such conditions fall shockingly short of acceptable healthcare standards.

“In the wards, most of the mattresses are not in good condition. The available chairs are also dangerous for users. Important equipment to handle emergencies and other cases is not available. It’s the reality at the hospital, and that’s why we have fewer to no patients at all,” a nurse, who craved anonymity, said.

Others not spared

For residents of Igbara-Oke, these stories are all too familiar. The emergencies that could have been resolved with timely intervention turn fatal before help arrives.

The general hospital that should serve as their lifeline often stands as an empty shell. On several occasions, critical drugs are not on the shelf, and in the worst moments, doctors are unavailable.

On 19 May 2025, in the same community, Shoky, a popular middle-aged man known for his cheerful nature, set out that morning, unaware he would not return home alive.

Miles from his house, his motorcycle collided with another vehicle. The crash left him soaked in his own blood, with his breath shallow and eyes fluttering between life and darkness.

In panic, bystanders rushed to his aid and lifted him into the back of a passing bus that served as an ambulance in his hour of need. Within minutes, they took him to Igbara-Oke General Hospital, which was his nearest hope for treatment.

Instead, it became another dead end. The emergency care his broken body demanded was not available. His family was handed a referral slip.

With no choice, his family set off again, this time on a one-hour journey to Akure, where hope of better care and his life hang in the balance. Every bump on the road wrung a groan from Shoky’s fading strength. After hours in different government facilities in Akure, relief never came.

He was transferred yet again to the Federal Medical Centre, Owo, where all that was left of him was a body drained of fight. By the time he was wheeled into the ward, it was too late.

“Normally, it takes only a few minutes to get to Igbara-Oke General Hospital. It’s just within walking distance. Yet, despite its proximity, the government facility couldn’t attend to him properly that day. There was no doctor to handle his case.

“The unavailability of doctors and proper equipment has caused many to die needlessly. Deaths that should have been prevented,” Shoky’s younger brother told our correspondent in an emotion-laden voice.

His death was not just the result of an accident but of a system that failed him at every turn, where delays and inadequate care turned survivable injuries into a needless tragedy.

Over the years, residents of Igbara-Oke and neigbouring villages like Amaye, Asae, Ilero, Imokuti, Odo-Oja, Ayetoro, Odo-Esi, Ogbontitun, and Otalo-Gboido, among others, have decried the state of the hospital due to lack of equipment, unavailability of needed drugs and consumables.

Added to this unpleasant state of the facility is the shortage of medical personnel to care for patients.

Findings revealed that the failure of the only general hospital has pushed residents into a dangerous reliance on the primary health centre.

While those who are well aware embrace the PHC, others rely on alternatives that offer little certainty, including traditional healers and herbal concoctions.

With the hospital barely functional, many residents told our correspondent that they had no choice but to embrace these risky options.

Sharing her ordeal, a resident, Funmi Olaoke, explained that the state of the hospital inspires fear rather than hope.

“This place is supposed to save lives, but the sight alone discourages you. Every time people go there, they don’t always get the care they need.

“Nothing works there. When I took my son there, even water is scarce, not to talk of other essentials,” the mother-of-two said.

Also, a civil servant with the revenue collection board, who visited the hospital to seek medical care for persistent hip pain due to the nature of his job, told our correspondent that nothing works in the hospital.

He said that without conducting a proper test, drugs were prescribed for him, adding that the hospital pharmacy has none of the prescribed drugs.

He added, “Even as a civil servant, I can’t rely on them. Nothing works there. The drugs that were prescribed for me after my complaints were not available at the pharmacy. I still went back to buy drugs in town, drugs that the hospital should have provided.

“They deduct money from our salaries monthly under the civil servant health scheme, but when you need medical help here, there’s nothing. This hospital issue is why I sometimes buy drugs for my children out of pocket. Many people are suffering.

“Many people, out of frustration, turn to chemists and roadside medicine sellers, who also exploit them. If you go to buy a drug that should be N3,000, they tell you N8,000 or N10,000. This is the reality; it’s a real crisis.”

For another resident, who simply identified himself as Segun, his experience of seeking care at the town’s general hospital still leaves a bitter taste.

After sustaining injuries from a motorcycle accident that refused to heal, he was advised to get a tetanus injection at the hospital.

He narrated, “When I had a motorcycle accident, and I went there after the injury I sustained wasn’t healing properly. I was advised to go to the hospital to get a tetanus injection. When I got there, I was directed to a chemist (local parlance for pharmacy) where I paid N2,000.

“I heard the chemist was being supplied by staff from the hospital who, in turn, get a commission from the money. Sick people around here do go through a lot; only God is saving us.”

What struck him most, however, was the darkness that enveloped the hospital.

“I have never heard of a hospital without light. At the general hospital, it’s been over two years since they had light,” he added.

Meanwhile, a nurse at the hospital confirmed Oladipo’s observation about electricity, saying, “We have been using solar as an alternative source of power. It has been a while now, and I don’t know why we are cut off from our normal power supply”.

Igbara-Oke hospital not isolated

Speaking with our correspondent, a nurse in the state maintained that the reality at Igbara-Oke was not an isolated case, adding that our corresponding findings depict the worsening conditions of government-owned hospitals across the state.

The nurse decried the state of healthcare in Ondo, describing it as deplorable and neglected for years.

The health worker, who spoke under anonymity condition, lamented that the decay is evident even from the headquarters of the Health Care Management Board.

“The state of health care in Ondo State is quite disgusting. This is because the sector has been neglected for a very long time. Starting from the Health Care Management Board headquarters, when you look at the structure, you already see the problems, and when you visit the hospitals, you meet worse conditions,” the source said.

According to the source, many of the state’s secondary health facilities are in ruins.

“Many of the state’s secondary health facilities are dilapidated. The equipment is not available or not functioning, and even the personnel are nothing to write home about, especially the nurses and doctors. A number of them have retired, others have resigned, and up till now there has been no adequate recruitment to fill these gaps,” the nurse said.

Furthermore, the source explained that many facilities operate without doctors for long hours.

“In many hospitals, there is often no doctor on duty because one doctor may be covering 24 hours alone. Nurses sometimes work 72 hours at a stretch or continue morning, afternoon, and night shifts for one week without proper rest. Some nurses have not gone for annual leave in years.

“Many wards have also been merged due to staff shortages. For example, where you used to have separate male and female medical or surgical wards, they are now merged into one. This is what patients encounter daily—it’s not mere hearsay,” the nurse said.

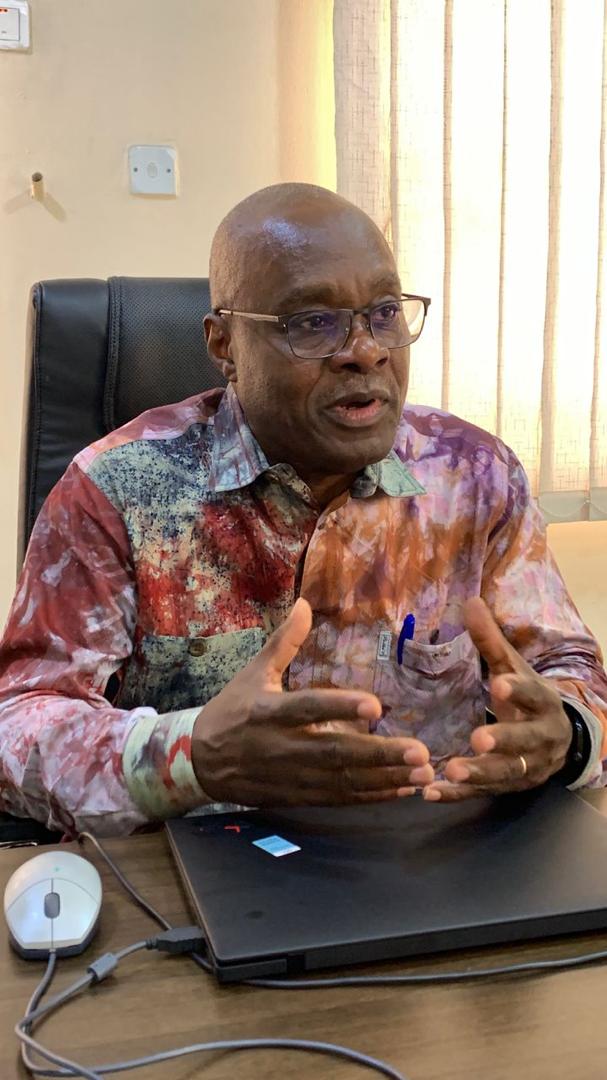

Medical director reacts

When PUNCH Healthwise reached out to the Igbara-Oke General Hospital’s Medical Director, Dr. Boye Balogun, on the issues around the hospital, he referred our correspondent to the hospital management board, saying the HBP controls all hospitals in the state.

“We have the management board at the headquarters, called the Hospital Management Board, and it is that board that controls all the hospitals,” he said.

The MD clarified that, contrary to claims, the pharmacy at the facility was operating optimally.

“Of course, there are drugs. They (pharmacist) have their prescription sheets, they record, and they check what is in stock and what is out of stock. It is not something hidden.

“If the doctor prescribes, the patient takes the prescription sheet to the pharmacy, and the pharmacist dispenses. The sheets are in duplicates—one copy stays with the pharmacy, and the patient keeps the other.

“It’s something anybody can verify. The documents are available.

“We are not the ones buying drugs directly. We have the hospital management board that oversees procurement. They know where to purchase drugs, and we buy regularly every month,” the hospital boss said.

Furthermore, Balogun maintained that issues bordering on inadequate personnel and staffing had been worsened by the mass emigration of health workers.

He noted that the entire health sector is being affected, stressing that since tertiary and specialist facilities are hard hit, secondary facilities like Igbara-Oke can’t be spared.

“This ‘japa’ syndrome has affected all health sectors—including teaching hospitals and tertiary centres, not to talk of secondary health facilities, where will you get the doctors? Where will you get the nurses? The senior staff, top-level doctors, are the ones remaining; the younger ones are leaving after their youth services. After house officers finish, they also leave.

“So, staffing is not really our problem. If you want to talk about staffing, go to the Hospital Management Board or speak directly to Mr Governor,” he said.

The medical faulted claims that patients are asked to provide petrol for the facility’s generating set, clarifying that the hospital was being powered by inverters with no power disruption.

“We have a very massive inverter power system. If you look at the building facing the gate, you will see the number of solar panels on the roof. In fact, the entire roof has solar panels.

“When you get to the main block, you will see that there is constant light. When you go to the general ward, you will see the massive inverter that serves it. So, for somebody saying they are buying fuel, I don’t think that is true.

“If you move around the wards, when you enter the maternity ward, you will see it is served by the general ward inverter.

“We also have an X-ray unit, and as massive as the X-ray unit consumption is, the inverter powers that X-ray machine. So, if anybody is saying they are buying fuel, I don’t think that is correct. We have inverters that run 24 hours a day,” he said.

However, when our PUNCH Healthwise reached out to the Ondo Ministry of Health’s Director, Hospital Services, Dr. Victor Adelusi, he said all questions should be directed to the Commissioner of Health, Dr Banji Ajaka.

“You should talk to the commissioner. I’m not allowed to talk to the press. The commissioner would be able to address all the issues you raised,” he told PUNCH Healthwise.

But when our correspondent reached out to the commissioner on September 18, calls to his line rang out twice. PUNCH Healthwise, however, sent him a message via WhatsApp detailing the investigation’s findings and sought the government’s reaction, but no response was received on Thursday night.

However, when our correspondent called the commissioner on September 19, he immediately acknowledged that he had seen the messages and read the content.

When PUNCH Healthwise pressed for his response, he clarified that he prefers a one-on-one interview rather than a phone interview.

“Yes, I saw your questions. I don’t like granting an interview on the phone. I don’t have anything to hide… I would have preferred we sit down and discuss, and I will give you evidence,” he said.

Speaking further, he explained that Igbara-Oke General hospital has many doctors.

“Your claim isn’t correct about Igbara-Oke hospital. You said there is no doctor there, but as I speak with you, I can tell you how many doctors we have in Igbara-Oke.

“Anyway, I’m in the middle of a meeting, and I can assure you I will respond to your questions. Either I call you back for us to speak, or I will reply in writing,” he said.

But when our correspondent reached out to him again after two hours, his line was unreachable, and a reminder message sent to his WhatsApp was yet to be responded to as of the time of filing this report.

SOURCE: PUNCH Newspaper